tl;dr

- Calculating the true cost of ownership of my co-op apartment in New York is complicated, as I have to factor in the $10,000 SALT Cap, standard vs itemized deductions, multiple state rules reducing deductions, differing tax laws at the state and federal level, tax credits, and plenty more.

- I calculated that I had $27,749 in mortgage payments, $21,516 in maintenance fees, $654 for insurance, and $264 for repairs in 2023, for a total cost of $50,183.

- Of those, I got back $14,238 in mortgage principal, $4,272 in tax refunds from deducting mortgage and property taxes, $379 in additional refunds connected to switching from the standard deduction to itemizing, and $284 in tax credits, for a total of $19,173. That netted out to a total of $31,010 in “lost” money, for a monthly “cost” of $2,584 to own my apartment (pretty good rent for Manhattan!).

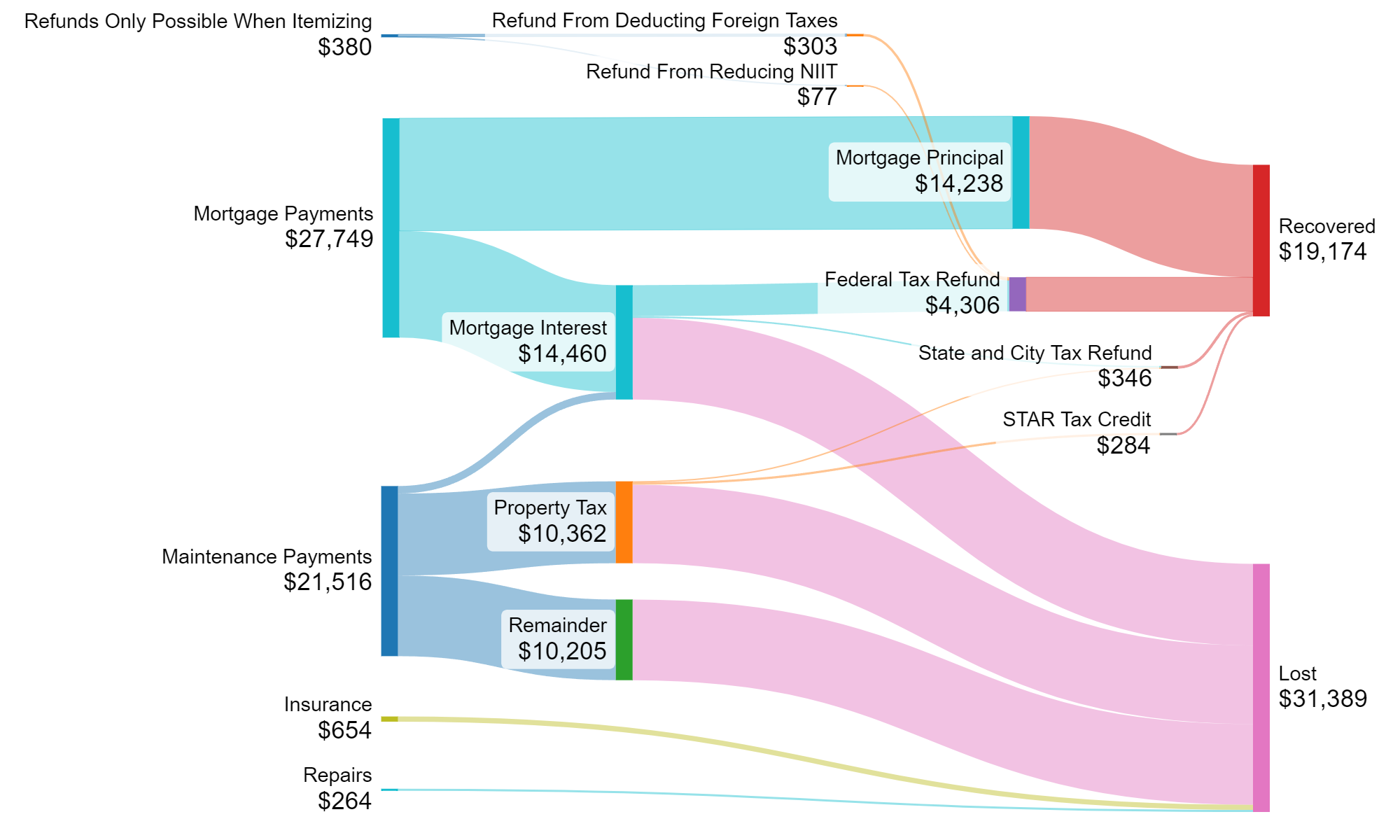

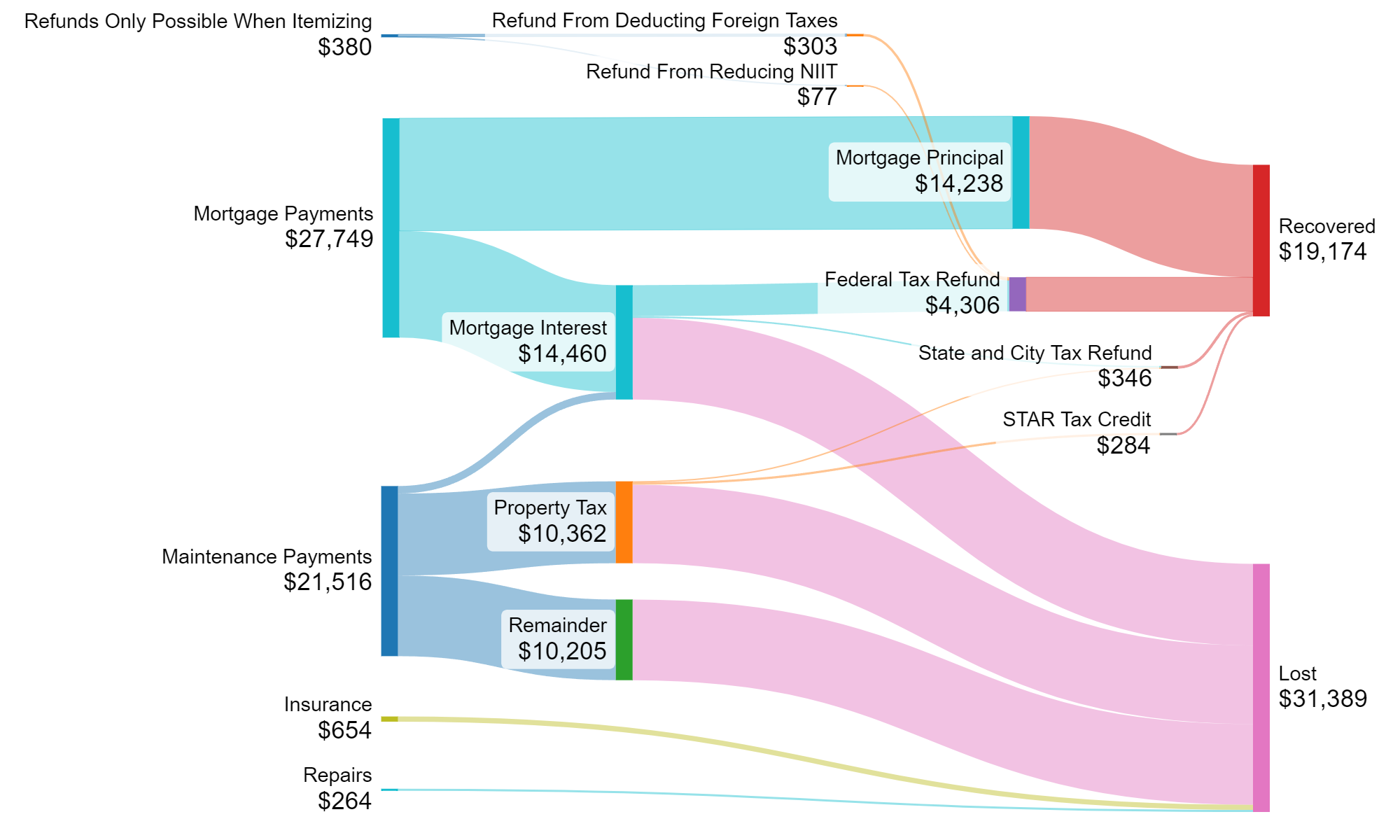

- Visualized, it all looks like this (interactive version):

Background

I bought an apartment in 2021, and my partner moved in with me. She wanted to split the “rent,” but I didn’t think it made sense for her to be paying 50% of my monthly mortgage and maintenance fees (like “condo fees,” but for a co-op) because not all of that money was being “lost;” some of it was going to be “recovered” in various ways. Instead, I wanted to figure out how much I “lost” when paying the various costs associated with owning the apartment, and then half that amount would be her share of the “rent”.

This post outlines my current understanding of the costs of owning my New York City co-op apartment. Note that it doesn’t account for any improvement costs, like the renovation or upgrades we’ve done.

Methodology

I started writing this post from first principles, using my understanding of finance and tax law. I kept thinking of more edge cases and complexity, so in the end I settled on this methodology to build confidence in the top line numbers:

- Start from my 2023 tax return in TurboTax and note down federal and state refund amounts.

- Delete only the mortgage interest and property tax deductions mentioned in this post.

- Note down the change in federal and state refund amounts.

I then followed those deltas backwards through dozens of tax forms until I could satisfactorily explain every penny that changed in my return.

Starting Costs

Things start off looking simple. I make three payments every month:

- Mortgage Payment ($27,749 / year): This is a single payment, but has two components: principal (ie. the amount that goes to reducing my outstanding loan balance) and interest (ie. the amount that I pay the bank1 as a return on their investment). The ratio between the principal and and interest shifts every month, but over the course of 2023 I paid $13,511 in interest and $14,238 in principal.

- Maintenance Fees ($21,516 / year): Maintenance fees cover all the costs of running my building. For the purposes of our calculations here, they have three main components:

- Property Tax: The co-op pays property taxes on my behalf, as a part of the maintenance fees. Those tax payments, however, are fully attributed to me for tax purposes. I am able to get property tax credits, and at the end of the year I am able to claim these payments on my tax return. For 2023, the co-op paid $10,362 in property taxes on my behalf, using my maintenance fees.

- Mortgage Interest: My co-op corporation also has a mortgage2. Like the property taxes, I get credit for the interest paid via my maintenance payments. For 2023, the co-op paid $949 in mortgage interest on my behalf.

- Everything Else: The co-op pays for our staff, building operations, water, heating, internet, and plenty of other things. This accounts for the remaining $10,205 in maintenance fees for 2023.

- Insurance ($654 / year): Home insurance was a requirement for getting my mortgage, and I generally think it’s worthwhile to protect an investment as large as my apartment. I currently pay $654 for insurance every year.

On top of monthly recurring payments, the other major cost of ownership is repairs. Luckily, we haven’t had any major issues, like having to replace an appliance. For smaller issues, I’m a fairly handy person, and do most repairs myself. Consequently, I only ever have to pay for parts, making our repair costs fairly small. In 2023, I paid $264 for parts3 to repair my oven, sink, toilet, tile grout, front door, stair tread, toilet again, and trellis. The one time I did call a professional to look at the oven, I was quoted $200 for the visits + parts, so things can be a lot more expensive if you don’t like to DIY.

What is “lost” and “recovered”?

I think of money as “lost” when I won’t get it back in any way shape or form. I think of it as “recovered” when it finds it’s way back to me in the form of equity, tax credits, etc. The next sections lay out which portions of my costs come back to me in one way or another.

Mortgage Principal

This one is the simplest. The $14,238 in principal payments are $14,238 more of equity in my home. There are lots of factors to consider if investing in real estate is the right move overall, all of which are beyond the scope of this post. For now, I’ll just argue none of this money is “lost;” it’s just deferred. It comes back to me whenever I choose to sell the house (assuming it hasn’t dropped in value).

Mortgage Interest

Mortgage interest doesn’t come directly back to me like principal payments do, but interest on the first $750,000 of mortgage debt is tax deductible at the Federal level, and interest on the first $1,000,0004 in debt is deductible at the New York (state and city) level. Being tax deductible essentially means that you remove it from your income when calculating how much you owe in taxes (the net number is your taxable income). Simplistically, if you owe 50% of your income in taxes, deducting $10,000 would reduce your taxes by $5,000.

A wrinkle in the deductibility of mortgage interest is that it requires you to itemize your deductions, rather than take the standard deduction (which is $13,850 Federally and $8,000 for New York, when filing single for 2023). For itemizing deductions to be better than taking the standard deduction, the deductible expenses that you have must add up to more than the standard deduction. For this blog’s target audience, their biggest deductible expense is probably their State And Local Taxes (SALT), assuming they live in a state with income tax. The problem is that federal tax law has a $10,000 SALT tax deduction cap. That cap means that the next $3,850 in deductions you do after your SALT deductions are just getting you back up to the deduction you could have gotten with the standard deduction. If you have less than $3,850 more in deductions, it’s usually not even worth itemizing. In my case, if I didn’t have mortgage interest, I wouldn’t have had $3,850 more in deductions to make itemizing better than taking the standard deduction. Thus, even though I had $13,511 + $949 = $14,460 in mortgage interest paid, I’m only really getting a tax advantage from reducing my federal income by $14,460 – $3,850 = $10,610 relative to the scenario where I would have taken the standard deduction.

New York also has a few tricky limits on itemized deductions that applied to me (there are also others that didn’t; this law is complicated):

- New York doesn’t have the SALT cap, but unfortunately they force you to subtract your state, local, and foreign income taxes from your itemizations.

- They reduce the amount you’re allowed to deduct by 3% of your income (Federal AGI) over $313,200 (for those filing Single).

- For whatever deductions you do calculate, they cut it in half if you earn $525,000 to $1,000,000.

The net result from 2) was that my $14,160 in mortgage interest was reduced to $13,2315. Then 3) further halved my deductible amount to $6,616. The New York standard deduction is $8,000 (filing single), meaning that I get no New York tax benefit from paying my mortgage interest alone; if it was my only itemizable expense, taking the standard deduction would have been better than itemizing. When factoring in that I also had property tax deductions to itemize, however, I calculated that this mortgage interest ended up accounting for a $1,901 deduction in my New York taxable income (see the “Property Taxes” section for the calculation).

The end result is: Having paid this mortgage interest, my federal taxable income is reduced by $10,610 and my New York taxable income is reduced by $1,901, relative to what it would have otherwise been.

When reducing your taxable income, the tax savings are applied at your highest marginal tax bracket (ie. if you owed 25% on income over $50k and 50% on income over $100k, reducing your income from $120k to $110k would save you 50% of $10k in taxes; the lower brackets don’t matter unless the deduction drops you a bracket). For me:

- My 2023 Federal marginal rate was 37%6, meaning that $10,610 reduction in federal taxable income got me $3,926 back in tax refunds.

- My 2023 New York State marginal rate was 6.85% and my New York City marginal rate was 3.876%, meaning my $1,901 reduction in state taxable income got me $204 back in tax refunds.

Combining the two, of the $14,460 in mortgage interest I paid, $3,926 + $204 = $4,130 came back to me through higher tax refunds, and the remaining $10,330 was “lost.”

Property Taxes

Property taxes are subject to the $10,000 Federal SALT cap discussed above7. Given that I already have over $10,000 in state taxes, I get zero additional reduction in my federal taxes from paying $10,362 in property taxes.

At the New York level, however, I get two benefits8:

- I got a $284 STAR tax credit9, that offsets my property taxes slightly.

- I was able to deduct my property taxes, reduced by the STAR credit ($10,362 – $284 = $10,078), on my New York tax return.

As we saw in the previous section, itemized deductions are complicated in New York. My $10,078 in property taxes was reduced to $9,220 and then further halved $4,611, before I could actually deduct it (following the same logic as the mortgage interest deductions discussed above). The deductible property taxes plus deductible mortgage interest from above is $4,611 + $6,616 = $11,226. That number is higher than the $8,000 (filing single) standard deduction. So property taxes plus mortgage interest reduced my New York taxable income by $11,226 – $8,000 = $3,226, relative to what I would have gotten from the standard deduction. If I allocate that proportionally to the two, I can say property taxes reduced my New York taxable income by $1,325 and mortgage interest reduced it by $1,901. Using the 6.85% and 3.876% state and city tax rates from above, that $1,325 taxable income reduction resulted in $142 more back on my taxes.

Combining the two, of the $10,362 in property taxes I paid, $284 + $142 = $426 came back to me through credits and refunds, and the remaining $9,936 was “lost.”

Everything Else

Insurance payments, repairs10, and the non-deductible portion of my maintenance fees are all “lost.” I don’t get them back in any form of credit or financial benefit.

Adding these other expenses together gets us to $10,205 + $654 + $264 = $11,123 in “lost” money.

Additional Benefits of Itemizing

Unlocking Deductions Less than the Standard Deduction

If prior to the mortgage interest you had some deductions to make (eg. charitable contributions), but they added up to less then $3,850 difference between the $10,000 SALT cap and the $13,850 standard deduction, they would have offered you no benefit on your taxes. By switching to itemizing your deductions, you all of a sudden get to benefit from those other deductions. For me, I had $818 in foreign tax deductions in 2023 that would have been lost if I hadn’t itemized my returns. Being able to use this deduction resulted in an additional $818 * 0.37 = $303 back on my federal return.

Unlocking NIIT Deductions

Switching from the standard deduction to itemized deductions enables me to use my deducted state and local taxes (still subject to the SALT cap) to reduce my Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) liability. NIIT is a 3.8% tax that applies to all investment income (eg. capital gains, dividends, interest) for individuals making over $200,00011. A simplified example of how this works is that if your investment income is 10% of your overall taxable income, you can attribute 10% of your itemized and deducted taxes to reducing your taxable investment income. For me, the total benefit worked out to $77.

Conclusion

I had $27,749 + $21,516 + $654 + $264 = $50,183 of apartment ownership expenses this past year, and $14,238 + $4,130 + $426 + $303 + $77 = $19,173 that came back to me in the form of equity and tax refunds. Thus, the net cost of owning my apartment this year was $31,010 (or $2,584 / month, which is a pretty good rent for Manhattan!). You can see and play with the numbers in spreadsheet form here. Visualized, the final result looks like this (interactive version):

- In reality, due to the securitization of mortgages it could be depository institutions, the Federal Reserve, mutual funds, money market funds, or any number of other investors that actually receive my payments. See Section 2.2 here for a nice breakdown. ↩︎

- It’s an interest only mortgage, taken out a few years before I bought my apartment, presumably for cash flow purposes. It is secured using the value of the common areas of our building, as well as the commercial rental units in the building. ↩︎

- For those interested, the full list is: $58.15 for a replacement igniter for my oven, $13.60 for CLR for a clogged faucet head, $14.93 + $8.33 + $4.38 for parts to rebuild the fill valve on the toilet, $13.84 for grout to repair cracks in the bathroom, $11.70 for replacement screws for our door handle, $14.39 + $9.99 for tools and parts to repair a stair tread to our back terrace that was detached, $16.90 for a replacement toilet flush handle, and $98.54 for tools to tear down a rotting trellis bolted to the walls of my terrace. ↩︎

- These caps used to be the same, until the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the cap on mortgage loan interest deductibility. Prior to this law, New York State was fairly closely aligned with Federal Law on income tax itemized deductions. After this law, New York decided to allow filers to itemize their taxes regardless of whether they itemized their federal taxes, and to use the pre-TCJA rules (which is where the $1,000,000 cap comes from). ↩︎

- To calculate this, I took the amount in Box 9 of the IT-196’s Total Itemized Deductions Worksheet, and divided it by the amount in Box 1. This effectively told me the percentage which all my deductions were being reduced by, assuming I evenly spread the reduction across all deductions. I think that this even spread methodology is reasonable, given that that is effectively what the Box 41 Worksheet is doing when it calculates how much to reduce your itemized deductions by when subtracting taxes. ↩︎

- FICA taxes (social security and medicare taxes) are also federal taxes. While they are substantial, at 6.2% for Social Security, 1.45% for Medicare, and a 0.9% Additional Medicare tax, they aren’t affected by income tax deductions. Your “medicare wages” (Box 5) and and “social security wages” (Box3) on your W2 determine how much you owe, and those can’t be reduced with itemized deductions of mortgage interest. ↩︎

- There has been plenty of speculation that the unique structure of co-ops might provide a SALT cap workaround. Unfortunately, the IRS has taken the position that that workaround is not allowed. ↩︎

- There is a third benefit, the Cooperative and Condominium Tax Abatement, which co-ops must apply for on behalf of their tenants. My co-op applies for this, then keeps it and uses it to reduce the property taxes attributed to my maintenance payments. The $10,362 in property taxes attributed to my maintenance payments in 2023 should already be reduced by the abatements the whole building received. ↩︎

- Unfortunately (well, in the grand scheme of things, fortunately), I won’t be eligible for this credit this year due to a RSU-driven increase in my income. ↩︎

- Note that improvement to a home will increase your cost basis, which can come back to you as tax savings when you sell. Repairs, however, do not count towards adjusting your basis. ↩︎

- Using your Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), not Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), because the IRS likes making things complicated… ↩︎

Leave a comment